Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through the book links and make a purchase.

Spoilers for both Mexican Gothic and Annihilation lie ahead. Tread wisely. These novels are worth reading unspoiled.

In 1950s Mexico City, 22-year-old socialite and aspiring anthropologist Noemí Taboada receives a bizarre letter from her cousin. Catalina recently married the mysterious Virgil Doyle and moved to a remote former mining town in Hidalgo. Now she writes:

This house is sick with rot, stinks of decay, brims with every single evil and cruel sentiment…

Mexican Gothic, p. 7

Catalina writes her own name multiple times as if to keep herself from forgetting it. Is Catalina mentally ill, or is she right that her new husband’s house is toxic? Noemí heads to the Doyle family home to unravel that mystery. There, she discovers she herself is not immune to the subtle poisons of High House. She begins to sleepwalk, dream vividly, and even speak to the ghosts in the walls.

That night she dreamed that a golden flower sprouted from the walls in her room, only it wasn’t…she didn’t think it a flower. It had tendrils, yet it wasn’t a vine, and next to the not-flower rose a hundred other tiny golden forms.

Mushrooms, she thought…

Mexican Gothic, p. 55

In Mexican Gothic, author Silvia Moreno-Garcia explores how one man’s ambition for immortality has driven him to inhumane acts.

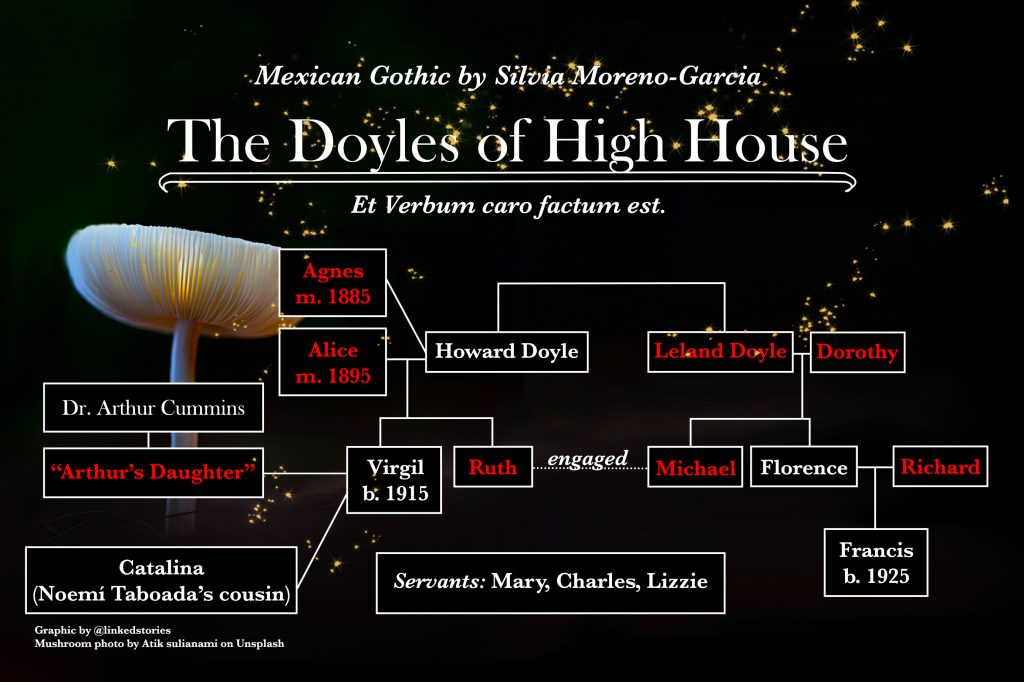

Once upon a time, Howard Doyle, Virgil’s father and the family patriarch, learned of the healing properties of an indigenous mushroom; it was so powerful it could extend life–maybe even grant immortality. Over the centuries, he used incest and cannibalism to combine his family’s bloodline with this mushroom. Eventually, the Doyles become irrevocably intertwined with the fungus that grows throughout the gloomy, decrepit High House. Every breath they take contains its spores and further binds them to it.

When Doyle installs the body of his dead wife Agnes as the host “mind” of the fungus, his immortality engine is complete. He has created a fungal neural network that he can use to preserve his memories and transfer his consciousness to other bodies.

The Doyle family crest is the ouroboros, a snake eating its own tail. The ouroboros can symbolize renewal and eternal life. Here, it’s a grim emblem of Doyle’s ambition. It’s a closed circle of power that rejects outsiders, the insignia of a hunger so great that it uses violence, rape, and mental enslavement as the means to its ends.

Why did this cycle ever begin?

When Noemí encounters him, Howard Doyle affirms his belief in pseudo-scientific tracts on eugenics and racial purity. But his cruel plan took root long before eugenics was invented in the late 19th century. In fact, his “scientific” reasons are a mere ex post facto explanation for his ardent narcissism and racism.

Likewise, eugenics was invented to give a scientific foundation for the racism, xenophobia, and ableism that already abounded. Unsurprisingly, belief in eugenics flourished in the United States, Nazi Germany, and Mexico, places that were eager for a rationale to justify their bigoted practices.

Like the fungus, racism lives in the walls of our homes, and Noemí Taboada has to find away to burn it out.

Preservation of Self?

Reading Mexican Gothic, I was reminded of the lush, abundant, even overripe natural world of Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy. I was gratified to see other readers making the connection:

Annihilation, the first book in the Southern Reach Trilogy, is a fascinating comparison point for Mexican Gothic. Both books traffic in many of the same gothic motifs while approaching horror from different angles. In Mexican Gothic, Howard Doyle manifests all-too-human motivations–arrogance, fear of death–as he transforms natural processes–symbiotic relationships and reproduction–into nightmarish cycles that corrupt what it means to be human. He becomes so powerful that to some, he isn’t even human; he is a god. But Noemí has only to understand the situation to figure out a way to destroy him. In Annihilation, the nightmare is that humans are being transformed by an alien element whose motivations and methods we do not understand and thus cannot stop.

Annihilation’s narrator, an unnamed biologist, joins an all-female expedition into Area X, a part of the Florida panhandle that has been reclaimed by nature–and something else. An extraterrestrial element is transforming the landscape and its inhabitants, though it’s unclear how. Inside Area X, the narrator discovers a tunnel, which she instinctively refers to as a Tower. The underground Tower is a mirror of the lighthouse built on the coastline. Already, we are immersed in Gothic tropes: the secluded, haunted landmark (like High House), doubling (like the Doyles’ shared family features), and nature unbound.

(For ease of reading, I’ll call the narrator Ghost Bird, her husband’s nickname for her.)

The self is an assailable thing in both Annihilation and Mexican Gothic. Hypnosis, suggestion, and dreams (all gothic tropes as well) muddy the desires of the characters. In an early scene, Ghost Bird finds unusual writing on the wall of the Tower. Moments later, she has her first “taste” of contamination by Area X:

“Where lies the strangling fruit that came from the hand of the sinner I shall bring forth the seeds of the dead to share with the worms that…”

…

Triggered by a disturbance in the flow of air, a nodule in the W chose that moment to burst open and a tiny spray of golden spores spewed out… I thought I had felt something enter my nose…

Annihilation, pp. 23, 25

Like Noemí, she has been infected by fungal spores. She comes to call her contamination the “brightness” (similar to how the Doyles have gold in their eyes from the fungus). And the more time Ghost Bird spends in Area X, the less she is herself. Her DNA is changing. Can she remember who she is, separate from Area X?

Late in the novel, Ghost Bird finds a journal kept by her husband, who entered Area X before her. He writes about seeing his own doppelgänger and discovering that Area X literally makes copies of people. Seeing another version of himself made him question his own identity. He had the fleeting impression that he was dead, he was a ghost.

Echoes and doubles are a significant motif in Annihilation. What constitutes “the self”? Who is self, who is other? Are we both? One melds into the other. The idea of a border–of a beginning and an end–becomes an illusion. The ouroboros, a closed circle.

Catalina fought the dissolution of herself by holding onto her name. Noemí fought it through sheer will and with help from others. (And from a magical potion.)

But Ghost Bird isn’t like Catalina and Noemí. As part of the obscure governmental protocols for entering Area X, Ghost Bird must shed her real name. Ghost Bird embraces her anonymity. And, she realizes, she is not afraid of being taken over by Area X:

“[T]he psychologist said I had changed, I think she meant I had changed sides. It isn’t true–I don’t even know if there are sides, or what that might mean–but it could be true. I see now I could be persuaded. A religious or superstitious person, someone who believed in angels or in demons, might see it differently. Almost anyone else might see it differently. But I am not those people. I am just the biologist; I don’t require any of this to have a deeper meaning.”

Annihilation, p. 192

Like Noemí, Ghost Bird is an independent, scientifically-minded woman. But unlike Noemí, she is detached from society. She is an enigma to both her husband and her expedition leader, the psychologist. Ghost Bird thrives apart from others, in the wilderness. She is that most unusual person who would choose to head deeper into Area X, having accepted that what awaits her is not a traditional death but rather a further evolution into the fabric of Area X. It’s not an unusual choice for a woman who came to Area X not to find her husband but to know. The novel ends with her last journal entries. Implicitly, she will travel where the reader cannot follow. She will become a thing we cannot know.

A limitation (though not necessarily flaw) of the horror of Mexican Gothic is that we never lose our heroine. The reader experiences the horror of living in the Doyle house but avoids the horror of watching the heroine embrace evil. High House is repellent from the first, and Noemí remains unwavering in her desire to escape. As a proud Mexican woman with indigenous roots, Noemí is the perfect opponent for the racist, patriarchal Howard Doyle. And when Virgil Doyle tries to exploit Noemí’s Dionysian inclinations, she resists:

He was right that she liked to play, that she enjoyed flirting and teasing and dancing….and once in a while a coil of darkness wrapped itself around her heart and she wished to strike, like a cat.

But even as she was admitting this, even as Noemí knew that this was a part of her, she also knew it was not her.

Mexican Gothic, p. 260

She fights back when Virgil tries to rape her. Some people are incorruptible, Mexican Gothic implies. Undoubtedly, preserving our heroine’s self is what allows for a happy ending.

A Fate Worse Than Death

Amid the tragedy and murder in these novels, both signal that there is a fate worse than death: to lose one’s freedom. In each novel, the heroine encounters a human being who has been melded with the natural phenomena in such a way that they are kept trapped in its underground heart. Noemí encounters the dead Agnes in the tombs beneath High House. Agnes lies with a “screaming maw,” mushrooms arrayed around her head in a “crown, a halo, of glowing gold.” Though Agnes has been memorialized as “Mother” by the Doyle house, Noemí sees no prestige in that position:

“They buried her alive and she died, and the fungus sprouted from her body…”

The creation of an afterlife, furnished with the marrow and the bones and the neurons of a woman, made of stems and spores.

Mexican Gothic, p. 282

Similarly, at the base of the Tower is a creature named the Crawler, an amalgamation of the extraterrestrial entity and the former lighthouse keeper, who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Ghost Bird comes face-to-face with this lighthouse keeper, who has been utterly enmeshed in the other. She stops short at his expression of sorrow and ecstasy.

This man who now existed in a place none of us could comprehend… I envied him that journey not at all.

Annihilation, p. 187

It is a testament to how deeply these novels delve into the unconscious, I think, that both Noemí and Ghost Bird find these nightmarish humans deep underground in darkly holy sites, surrounded by a terrific buzzing sound.

These protagonists enter spaces that feel sacred, like the tombs where Agnes, the “destroying angel,” bears a halo, or in the depths of the Tower where “the brightness coiled within me…an almost hushed quality, as if we were in a cathedral” (p. 178). Noemí’s “fingers touched the drape [over Agnes’s body], and the buzzing became the beating of a thousand frenetic insects against glass…” (p. 281). Around the Crawler, Ghost Bird similarly hears noise “like a crescendo of ice or ice crystals shattering to form an unearthly noise that I had mistaken earlier for buzzing” (p. 176).

I was ensnared by their existential terror and the sound it made. This quote came to mind: “as if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced.” I was also reminded of the fear we, as individuals, might feel in becoming one with the hive.

This is the fate worse than death. Both Agnes and the lighthouse keeper are prisoners of their new environments, or perhaps, slaves to new gods.

An Afterlife

Whether or not it’s worth losing oneself in these nightmare worlds seems to depend upon the afterlife one anticipates. That afterlife might be eternal enslavement to someone like Howard Doyle, a sick remnant of the past. In that case, Noemí better fight back with everything she’s got.

Or what lies beyond the veil could be a pristine natural environment far removed from the modern world. It’s almost not the worst thing, Ghost Bird reasons, that Area X can’t be stopped. It’s a beautiful place. In fact, her bargain to explore further might not be so alien after all.

Additional Reading

“The Gothic Spaces of Annihilation,” Siobhan of the Dead, April 2, 2018.