Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through the Salvage the Bones link and make a purchase.

(Includes spoilers for Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward, published in 2011)

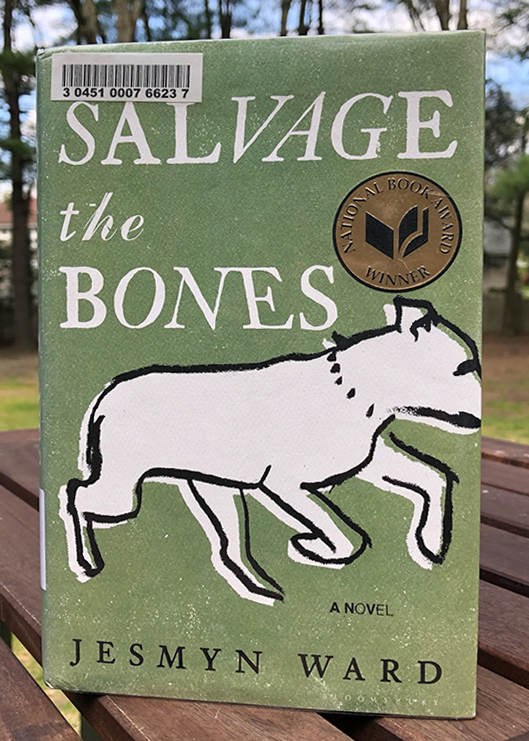

When I learned that Jesmyn Ward would speak during Amherst College’s LitFest 2020, I scooped up Salvage the Bones from the library. I planned to speed-read in time for the event. I could not. This novel demands that you dwell in each of its days.

Set in late 2005, the story follows Esch, a 15-year-old girl who lives with her father and three brothers in Bois Sauvage (translation: Wild Wood), a rural, impoverished Gulf Coast town. It’s a fictionalized version of DeLisle, Mississippi, where Ward grew up and now lives. The novel opens with two promises of life: Esch discovers she is pregnant. And her brother Skeetah’s pitbull China–a cherished, porcelain-white fighting dog–gives birth to a litter of puppies. In each chapter, a single day unfolds in the lead-up to the arrival of Hurricane Katrina.

“I lived through [Hurricane Katrina]. It was terrifying and I needed to write about that. I was also angry at the people who blamed survivors for staying and for choosing to return to the Mississippi Gulf Coast after the storm. Finally, I wrote about the storm because I was dissatisfied with the way it had receded from public consciousness.”

Jesmyn Ward, Paris Review

Those affected by Hurricane Katrina sometimes had their stories mediated by racially biased news reporting; survivors were even shamed for seeking assistance after their lives were swept away. And as Ward notes, it became easy for the nation to move on from this localized disaster. In the same way Ward’s white neighbor refused her family shelter, our collective memory has turned away the stories of Katrina survivors.

Ward’s extraordinary language reframes these “small” and “forgotten” lives as immense, worthy, even mythic. Here is Esch thinking about Manny, the father of her baby: “I imagine that this is the way Medea felt about Jason when she fell in love, when she knew him; that she looked at him and felt a fire eating up through her rib cage turning her blood to boil, evaporating hotly out of every inch of her skin. I feel it so strongly that I cannot imagine how Manny does not feel it, too.” It’s not “teenage love”–it’s Love, in all its terrible greatness.

In Bois Sauvage, love and violence are not opposing forces. They are bound together inescapably. In Ward’s hands, a dog fight becomes a battle of love, loyalty, and beauty: “There are pink mimosa flowers drifting and falling on the breeze,” as a young man cries out for his dying dog; the dog is “keening, and it is a song.” With her own mother dead, Esch observes China’s both tender and painful journey through motherhood. When China inexplicably kills her own puppy, “China is bloody-mouthed and bright-eyed as Medea. If she could speak, this is what I would ask her: Is this what motherhood is?“

Attending Ward’s event at Amherst College was one of the last gatherings I went to before the virus arrived in Massachusetts. Since my local library closed, Salvage the Bones has remained on my desk. I’m thinking now about how people react to a “visible” emergency and an “invisible” one. Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath killed almost 2,000 people and left millions more homeless. In Salvage the Bones, you can see what an emergency brings out in the characters. Trapped by floodwaters, the family has to break out of their attic and swim to safety nearby. This emergency demands quick thinking, physical bravery, and heroism. It’s visceral; it’s visible. Made memorable.

And yet, in the years following Hurricane Katrina, the colossal devastation has been made invisible by its distance in time and space from the rest of the country.

Meanwhile, in the face of an “invisible” emergency–the spreading of the novel coronavirus–I can’t help suspecting that many vocally non-compliant folks are in part underwhelmed by the protective measures we’ve been advised to use. If fighting this virus is like fighting a war, why are we being asked to wash our hands? they may ask. Shouldn’t we be arming ourselves instead? As my friend tells me, at the start of the pandemic, the security officers at her workplace (whose professions demand self-conscious bravery) teased those colleagues who first donned masks. I suppose it doesn’t feel manly to be careful. My own uncles, machistas now in their seventies, spend their days cruising around on errands and buying lottery tickets. I’m sure us mask-wearers look like a bunch of easily spooked wimps to them; meanwhile, to me they look naively convinced of their invincibility.

I myself had courage at the beginning of this crisis. I treated it like the arrival of a storm and did what I’d learned in my previous job among the “essential” employees of a medical center. I put together my emergency go bag, copied important documents, and stored up food for two weeks for both us and our dog. My husband and I discussed our evacuation plans should we be unable to reach each other at home. By the time panicked shoppers were cleaning out my supermarket, we were already prepared.

But of course, the storm landed silently. An invisible bomb, it decimated human activities and left the trees and wildlife intact. Through my window, I see extraordinarily green, freshly mown grass. My dog naps in the sun. The pandemic is real, but it feels like it’s only inside me, a greater gravity that drags me down.

What I feel now is an enfeebling anxiety. Will I touch my face at the grocery store? Will I get my husband sick? Will he get a colleague sick? Or will one of his patients give him the sickness that comes home to me? When will I see my parents again? I was a fool to not take a group picture at our last Christmas together. What kind of world will my friends’ babies, about to be born, discover?

So I can see why many may not be able to cope with the “invisible” emergency that elicits anxiety and instead choose to confront the visible “emergency.” That is, the so-called “emergency” of the government recommending face masks and social distancing and in doing so, trampling on “individual liberty.” (I’m using scare quotes because I don’t think it’s anyone’s right to endanger the public health.) Protesters must feel self-righteous, courageous, and even comforted in gathering with friends to battle what they can see (e.g. businesses closing as a result of social distancing) instead of doing the passive/anxious-making/wimpy thing of staying home to fight what they can’t see (the virus itself, and its obscured impact: the thousands sick in COVID-19-only wards and the morgues full of the dead).

And yet, there is another angle to non-compliance, as Ward’s novel reminds me. Marginalized communities are feeling the brunt of the pandemic just as they did the hurricane, just as they do every major disaster. And so, remembering Ward’s words, I must remind myself that the reasons for not complying with CDC guidelines today can be just as complex and nuanced as why some people choose not to (or simply cannot) evacuate during a hurricane. I must summon compassion where I can. Even the only widely available defense we have–social distancing–is not readily applicable by all, especially by those who would otherwise not be able to eat, or for whom home is not safe.

In Salvage the Bones, Skeetah struggles to keep China and her puppies alive. But one by one, they die. In the raging hurricane, he must choose whether to grab his drowning sister or his beloved China. He chooses Esch. The sacrifice is devastating. Once the rains have gone, Skeetah waits for China to come back to him. Esch waits with her brother. She imagines China’s return, when she and China will be sisters in their motherhood. In the stillness, Bois Sauvage remains a savage, beautiful place, where life and death move side-by-side.

The triumph of Salvage the Bones is how the storm unites the family. But the tragedy is that their unity has come at a tremendous cost–indeed, at the cost of almost everything else–and that the community at large–i.e. the rest of the country–doesn’t fully understand what has happened, and will forget.

Today’s storm is ongoing. In the midst of it, I hoped this country would draw closer together. Instead I see us drifting further apart, fifty individual states heading to our separate fates. I hope that we don’t. I hope we grab on to each other, hold on. That’s all we have in uncertain times, as we wait suspended in the eye of the hurricane. Hope. Hope enough to imagine the impossible.

Additional Reading

- “Jesmyn Ward on Salvage the Bones,” Paris Review, August 2011

- “My True South: Why I Decided to Return Home,” Time, July 2018